By: Luiza Vianna

Skeuomorphism (SKYOO-uh-mor-fiz-um), or a derivative object’s adoption of original design elements from its predecessor, has long been utilized in the development of new technology. A smartphone can provide multiple examples of this design phenomenon, especially if we think of the original iPhone: the calculator app had the layout of a physical calculator, the notes app resembled a yellow legal pad with handwriting-like font, the YouTube app icon mimicked a vintage television, the voice notes app showed an old-time microphone, and the clock app portrayed analog clocks. Well-known visual elements evoked in users a feeling of familiarity in a changing technological world.

Not all of these easily recognizable designs were kept but skeuomorphism is still present in our day-to-day technological tools. Many are seen in flatter versions for both aesthetic and operational reasons: the modern explosion of minimalist aesthetics and the ease of scalability across different devices (Gatsou and Farrington, 2021). Instead of bright lined paper and icons of vintage gadgets, we become accustomed to neutral shades and standardized shapes.

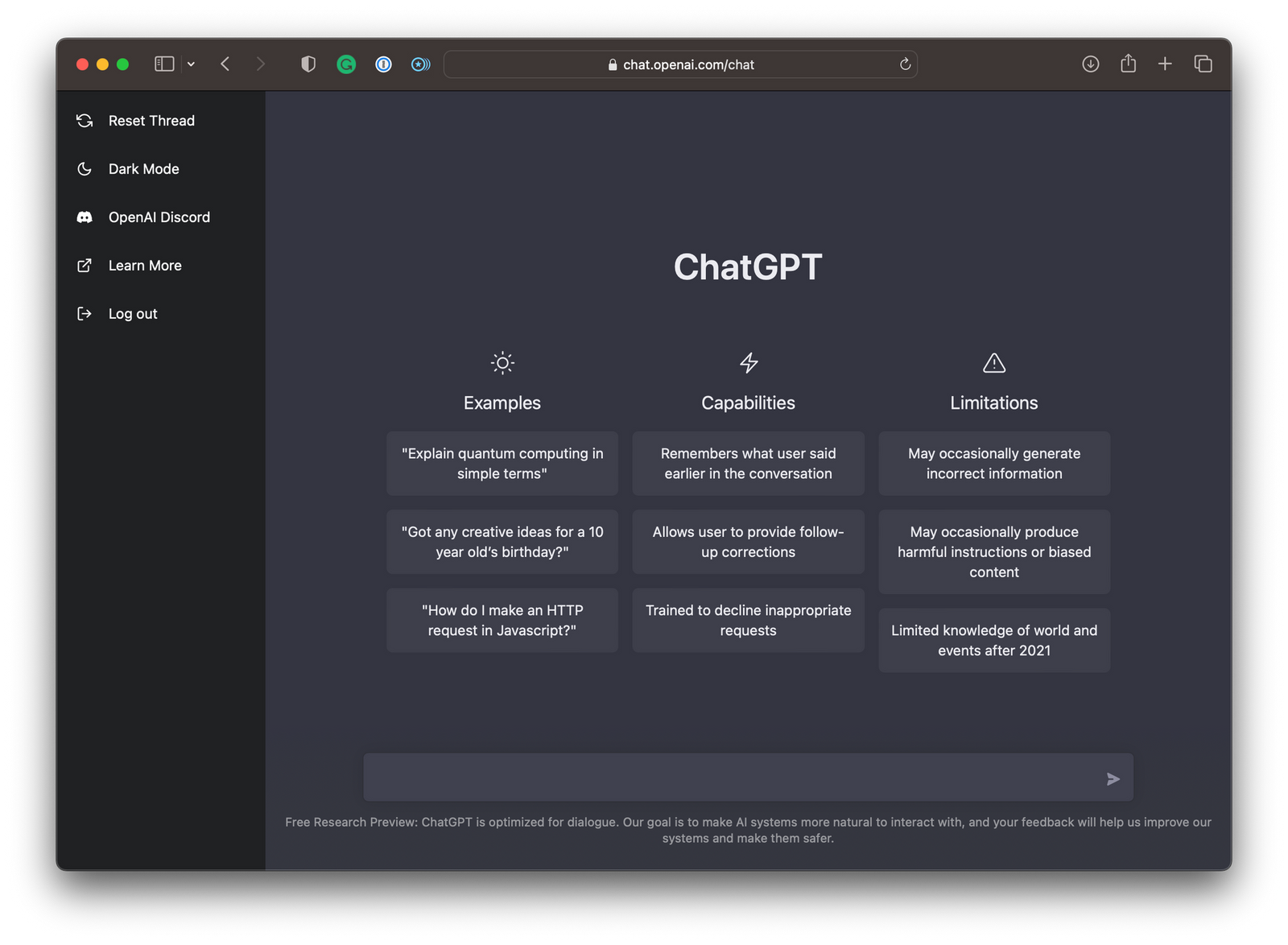

Artificial intelligence (AI) is not exempt from the perpetual use of skeuomorphism, but instead of utilizing only physical elements as inspiration, we now see familiar characteristics from the digital world as well. Chatbots mimic messaging interfaces with text bubbles, conversation history sidebars, and emojis. Notably, generative-AI assistants such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Copilot, only use the representation of speech-like text bubbles for the human element of the conversation, utilizing shape to induce realness of human input. Customer service or online help chatbots, on the other hand, envelop both sides of the conversation in text bubbles. There is no clear explanation for this phenomenon, but we can speculate that the former is meant to represent an entirely virtual assistant, while the latter, at many times, anticipates or substitutes a human customer service representative. Moreover, many chatbots interfaces showcase tabs on one side, drawing ideas from Google Docs, which in turn replicate physical notebooks. They also have a “dark mode” alternative, reminiscent of iPhone displays. It is intriguing that AI chatbots are considered a novelty but much of their interfaces are readopted digital designs.

As we move from physical to digital realms, incorporating online and AI versions of material elements, do we degrade every day experiences, attempting to maintain some semblance of originality though skeuomorphism? Or should we adopt object-oriented ontology ideals (Morton, 2011) and consider digital matter as its own object rather than an evolution of the physical? For now, “digital devices, whether smart objects, software applications, or media files, tend to be grouped into a single, ontologically homogeneous category of IT resource, and where such resources are often portrayed as straightforwardly physical things” (Faulkner and Runde, 2019), so it seems the discussion will remain open. Nevertheless, it is worth considering how AI chatbot platforms will impact the digital field and alter our perceptions of skeuomorphism.

References

Faulkner, P., & Runde, J. (2019). Theorizing the Digital Object. MIS quarterly, 43(4), 1279-1302.

Gatsou, C., & Farrington, J. S. (2022). The Evolution Of The Graphical User Interface: From Skeuomorphism To Material Design. Design/Arts/Culture, 2.

Morton, T. (2011). Here Comes Everything: The Promise of Object-Oriented Ontology. Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences, 19(2), 163-190.